DISCLAIMER: The article has been written by a human, so you will find grammatical errors and simple language.

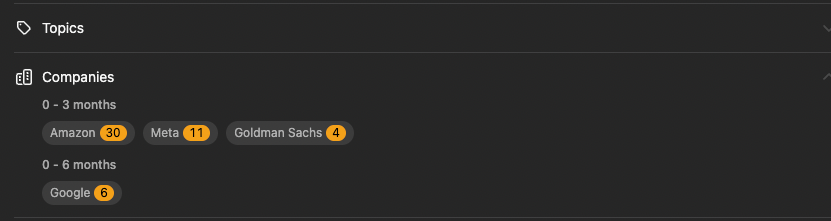

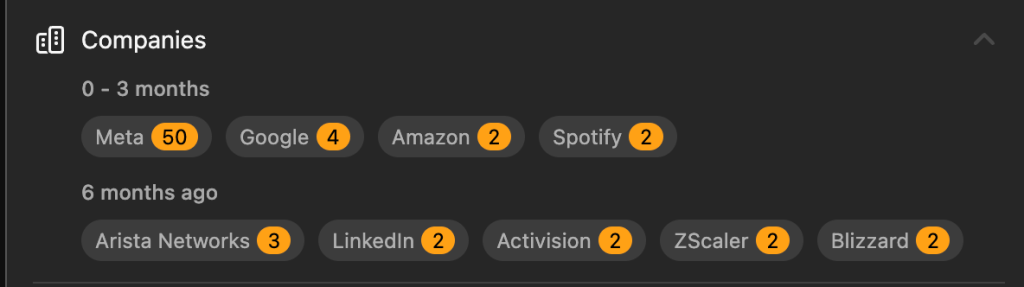

So OpenAI just launched GPT-5 and like you I’m also hyped, it’s faster, better and cheaper than 4o, 4.1 and o4 as their demo videos state and I’m fully on-board the hype train.

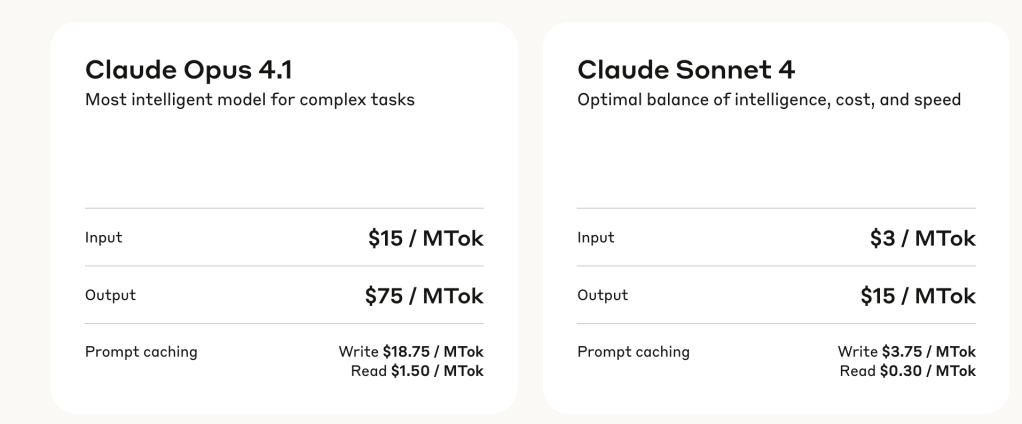

It’s cheaper than Claude Opus and Sonnet also on API pricing, not just cheaper but 10x cheaper than Opus and ~60% cheaper in input tokens when compared to Sonnet.

But the real question is, is it better than Sonnet or Opus. I tested both models out on specific tasks and compared their performance, both on speed and accuracy. These tasks are not your typical coding challenges, as we know that these models are much better at coding than average humans, so we test these with some bizarre requirements. We also test the API endpoints, as the ChatGPT interface is not a single LLM call but rather an Agent. So we get to understand, what we can build with these models.

TASK – Draw a Squirrel Riding a Cycle

This is not your typical image generation, the text endpoint has to create this image, using the SVG format, the thing about SVG format is that its based on XML, so it can be output as a text.

I’m using Pydantic-AI to invoke the APIs, in case you want me to cover a detailed guide on using Pydantic-AI to build agents, write in the comments below.

Prompt – “Draw a squirrel riding a cycle in SVG format, just return the xml.”

GPT-5

So GPT-5 consumed around 5k tokens and took 111.3698 seconds. The image it generated looks good. It looks somewhat like a squirrel and the cycle was I guess easy for it to draw.

There are some issues like spokes are missing and the attempt at shadow is off and the handles are missing, but it’s pretty impressive.

Usage(requests=1, request_tokens=21, response_tokens=4777, total_tokens=4798, details={'accepted_prediction_tokens': 0, 'audio_tokens': 0, 'reasoning_tokens': 2368, 'rejected_prediction_tokens': 0, 'cached_tokens': 0})

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="800" height="600" viewBox="0 0 800 600">\n <defs>\n <line id="spoke" x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="-65" stroke="#cfcfcf" stroke-width="2" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n </defs>\n\n <!-- Ground shadow -->\n <ellipse cx="260" cy="455" rx="95" ry="14" fill="rgba(0,0,0,0.12)"/>\n <ellipse cx="540" cy="455" rx="95" ry="14" fill="rgba(0,0,0,0.12)"/>\n\n <!-- Bicycle -->\n <g id="bicycle">\n <!-- Rear wheel -->\n <g transform="translate(260 420)">\n <circle r="80" fill="none" stroke="#222" stroke-width="10"/>\n <circle r="65" fill="none" stroke="#8f8f8f" stroke-width="3"/>\n <circle r="6" fill="#777"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(0)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(15)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(30)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(45)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(60)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(75)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(90)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(105)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(120)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(135)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(150)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(165)"/>\n </g>\n\n <!-- Front wheel -->\n <g transform="translate(540 420)">\n <circle r="80" fill="none" stroke="#222" stroke-width="10"/>\n <circle r="65" fill="none" stroke="#8f8f8f" stroke-width="3"/>\n <circle r="6" fill="#777"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(0)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(15)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(30)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(45)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(60)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(75)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(90)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(105)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(120)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(135)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(150)"/>\n <use href="#spoke" transform="rotate(165)"/>\n </g>\n\n <!-- Frame geometry points:\n Rear hub R(260,420), Bottom bracket B(365,420),\n Seat S(385,350), Head H(520,355), Front hub F(540,420)\n -->\n <!-- Chainstay -->\n <line x1="260" y1="420" x2="365" y2="420" stroke="#2c6b8a" stroke-width="8" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Seat stay -->\n <line x1="260" y1="420" x2="385" y2="350" stroke="#2c6b8a" stroke-width="6" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Seat tube -->\n <line x1="365" y1="420" x2="385" y2="350" stroke="#2c6b8a" stroke-width="8" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Top tube -->\n <line x1="385" y1="350" x2="520" y2="355" stroke="#2c6b8a" stroke-width="7" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Down tube -->\n <line x1="365" y1="420" x2="520" y2="355" stroke="#2c6b8a" stroke-width="8" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Fork -->\n <line x1="520" y1="355" x2="540" y2="420" stroke="#2c6b8a" stroke-width="7" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n\n <!-- Seat -->\n <rect x="360" y="335" width="55" height="14" rx="7" ry="7" fill="#333"/>\n <rect x="372" y="345" width="8" height="15" fill="#333"/>\n\n <!-- Handlebars -->\n <line x1="520" y1="355" x2="530" y2="350" stroke="#333" stroke-width="6" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <path d="M 530 350 C 546 344, 565 344, 580 352" fill="none" stroke="#333" stroke-width="7" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <line x1="579" y1="351" x2="586" y2="341" stroke="#555" stroke-width="7" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n\n <!-- Crankset and chain -->\n <circle cx="365" cy="420" r="28" fill="none" stroke="#555" stroke-width="6"/>\n <circle cx="365" cy="420" r="14" fill="#777"/>\n <!-- Crank arms -->\n <line x1="365" y1="420" x2="398" y2="401" stroke="#444" stroke-width="6" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <line x1="365" y1="420" x2="332" y2="439" stroke="#444" stroke-width="6" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Pedals -->\n <rect x="394" y="395" width="16" height="8" rx="3" ry="3" fill="#666" transform="rotate(-30 402 399)"/>\n <rect x="316" y="435" width="16" height="8" rx="3" ry="3" fill="#666" transform="rotate(150 324 439)"/>\n <!-- Chain to rear cog -->\n <path d="M 393 420 C 412 420, 240 421, 240 421\n M 393 412 C 412 412, 240 413, 240 413"\n fill="none" stroke="#5e5e5e" stroke-width="3" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Rear cog -->\n <circle cx="260" cy="420" r="12" fill="none" stroke="#666" stroke-width="4"/>\n </g>\n\n <!-- Squirrel -->\n <g id="squirrel" stroke-linejoin="round">\n <!-- Tail -->\n <path d="M 380 360\n C 330 340, 320 290, 355 265\n C 395 235, 460 280, 445 320\n C 437 341, 408 346, 396 338\n C 408 358, 395 372, 380 360 Z"\n fill="#C97E3A" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="4"/>\n <path d="M 392 332\n C 410 343, 433 333, 437 316"\n fill="none" stroke="#B8682F" stroke-width="3" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n\n <!-- Body -->\n <ellipse cx="400" cy="365" rx="48" ry="36" fill="#C97E3A" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="4"/>\n <!-- Belly -->\n <ellipse cx="395" cy="372" rx="26" ry="20" fill="#F5C78A" stroke="none" opacity="0.9"/>\n\n <!-- Head -->\n <circle cx="432" cy="330" r="24" fill="#C97E3A" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="4"/>\n <!-- Ear back -->\n <path d="M 420 308 L 408 292 L 424 298 Z" fill="#B8682F" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="3"/>\n <!-- Ear front -->\n <path d="M 442 307 L 455 292 L 448 311 Z" fill="#B8682F" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="3"/>\n <!-- Eye -->\n <ellipse cx="438" cy="326" rx="7" ry="9" fill="#fff"/>\n <circle cx="440" cy="328" r="4" fill="#222"/>\n <circle cx="441.5" cy="326.5" r="1.5" fill="#fff" opacity="0.8"/>\n <!-- Nose and mouth -->\n <circle cx="454" cy="336" r="3" fill="#3c1f12"/>\n <path d="M 450 340 Q 446 345, 440 342" fill="none" stroke="#3c1f12" stroke-width="2" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n\n <!-- Arm to handlebar -->\n <path d="M 410 355\n Q 450 352, 520 355" fill="none" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="8" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Paw on grip -->\n <ellipse cx="582" cy="352" rx="10" ry="7" fill="#C97E3A" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="4"/>\n\n <!-- Rear leg to pedal -->\n <path d="M 382 385\n Q 392 398, 398 401" fill="none" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="8" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n <!-- Rear paw on pedal -->\n <ellipse cx="402" cy="399" rx="9" ry="6" fill="#C97E3A" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="3"/>\n\n <!-- Front leg resting -->\n <path d="M 386 380\n Q 380 392, 370 402" fill="none" stroke="#8A4B20" stroke-width="7" stroke-linecap="round"/>\n\n <!-- Cheek highlight -->\n <ellipse cx="425" cy="340" rx="9" ry="6" fill="#F5C78A" opacity="0.7"/>\n </g>\n</svg>

Claude 4 Sonnet

I’m too broke to use Opus 4.1, so we shall compare Sonnet 4

<svg width="400" height="300" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">\n <!-- Bicycle wheels -->\n <circle cx="100" cy="200" r="40" fill="none" stroke="#333" stroke-width="3"/>\n <circle cx="250" cy="200" r="40" fill="none" stroke="#333" stroke-width="3"/>\n \n <!-- Bicycle frame -->\n <line x1="100" y1="200" x2="175" y2="160" stroke="#666" stroke-width="4"/>\n <line x1="175" y1="160" x2="230" y2="160" stroke="#666" stroke-width="4"/>\n <line x1="230" y1="160" x2="250" y2="200" stroke="#666" stroke-width="4"/>\n <line x1="175" y1="160" x2="175" y2="190" stroke="#666" stroke-width="4"/>\n <line x1="175" y1="190" x2="250" y2="200" stroke="#666" stroke-width="4"/>\n \n <!-- Pedals -->\n <circle cx="175" cy="190" r="5" fill="#333"/>\n <line x1="170" y1="185" x2="180" y2="195" stroke="#333" stroke-width="2"/>\n \n <!-- Handlebars -->\n <line x1="230" y1="160" x2="235" y2="150" stroke="#666" stroke-width="3"/>\n <line x1="225" y1="150" x2="245" y2="150" stroke="#666" stroke-width="3"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel body -->\n <ellipse cx="190" cy="135" rx="25" ry="15" fill="#8B4513"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel head -->\n <circle cx="210" cy="120" r="18" fill="#8B4513"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel ears -->\n <ellipse cx="205" cy="105" rx="4" ry="8" fill="#8B4513"/>\n <ellipse cx="215" cy="105" rx="4" ry="8" fill="#8B4513"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel tail -->\n <path d="M 165 140 Q 140 120 130 100 Q 125 95 135 90 Q 145 95 150 110 Q 160 130 165 140" fill="#A0522D" stroke="#8B4513"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel arms -->\n <line x1="200" y1="130" x2="240" y2="145" stroke="#8B4513" stroke-width="4"/>\n <circle cx="240" cy="145" r="3" fill="#8B4513"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel legs -->\n <line x1="185" y1="145" x2="175" y2="175" stroke="#8B4513" stroke-width="4"/>\n <line x1="195" y1="145" x2="175" y2="175" stroke="#8B4513" stroke-width="4"/>\n \n <!-- Squirrel face -->\n <circle cx="206" cy="118" r="2" fill="#000"/>\n <circle cx="214" cy="118" r="2" fill="#000"/>\n <circle cx="210" cy="125" r="1" fill="#000"/>\n \n <!-- Wheel spokes -->\n <line x1="100" y1="200" x2="120" y2="180" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n <line x1="100" y1="200" x2="80" y2="180" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n <line x1="100" y1="200" x2="120" y2="220" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n <line x1="100" y1="200" x2="80" y2="220" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n \n <line x1="250" y1="200" x2="270" y2="180" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n <line x1="250" y1="200" x2="230" y2="180" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n <line x1="250" y1="200" x2="270" y2="220" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n <line x1="250" y1="200" x2="230" y2="220" stroke="#666" stroke-width="1"/>\n</svg>

Usage(requests=1, request_tokens=25, response_tokens=1156, total_tokens=1181, details={'cache_creation_input_tokens': 0, 'cache_read_input_tokens': 0, 'input_tokens': 25, 'output_tokens': 1156})

Sonnet took like 15 seconds and only 1.2k tokens and honestly, despite having lesser details than GPT-5, it looks more in line with the prompt than GPT-5. The squirrel clearly looks like a squirrel and the cycle is with handles. So I’ll say that this is a tie in my opinion.

TASK – Draw a medium difficulty maze

Prompt -“Draw a medium difficulty maze in SVG format, just return the xml.”

GPT-5

GPT-5 took 6.1k tokens and 70 seconds

Usage(requests=1, request_tokens=20, response_tokens=6081, total_tokens=6101, details={'accepted_prediction_tokens': 0, 'audio_tokens': 0, 'reasoning_tokens': 5120, 'rejected_prediction_tokens': 0, 'cached_tokens': 0})

I don’t know about you, but this is more like an easy maze than a difficult one.

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="600" height="600" viewBox="0 0 600 600">\n <rect x="0" y="0" width="600" height="600" fill="#ffffff"/>\n <g stroke="#000000" stroke-width="10" stroke-linecap="square" fill="none">\n <!-- Outer border (with entrance on left and exit on right) -->\n <line x1="20" y1="20" x2="580" y2="20"/>\n <line x1="20" y1="20" x2="20" y2="60"/>\n <line x1="20" y1="100" x2="20" y2="580"/>\n <line x1="580" y1="20" x2="580" y2="540"/>\n <line x1="20" y1="580" x2="580" y2="580"/>\n\n <!-- Horizontal walls with alternating gaps to form a serpentine path -->\n <!-- y = 100, gap [520,560] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="100" x2="520" y2="100"/>\n <line x1="560" y1="100" x2="580" y2="100"/>\n <!-- y = 140, gap [40,80] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="140" x2="40" y2="140"/>\n <line x1="80" y1="140" x2="580" y2="140"/>\n <!-- y = 180, gap [480,520] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="180" x2="480" y2="180"/>\n <line x1="520" y1="180" x2="580" y2="180"/>\n <!-- y = 220, gap [80,120] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="220" x2="80" y2="220"/>\n <line x1="120" y1="220" x2="580" y2="220"/>\n <!-- y = 260, gap [440,480] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="260" x2="440" y2="260"/>\n <line x1="480" y1="260" x2="580" y2="260"/>\n <!-- y = 300, gap [120,160] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="300" x2="120" y2="300"/>\n <line x1="160" y1="300" x2="580" y2="300"/>\n <!-- y = 340, gap [400,440] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="340" x2="400" y2="340"/>\n <line x1="440" y1="340" x2="580" y2="340"/>\n <!-- y = 380, gap [160,200] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="380" x2="160" y2="380"/>\n <line x1="200" y1="380" x2="580" y2="380"/>\n <!-- y = 420, gap [360,400] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="420" x2="360" y2="420"/>\n <line x1="400" y1="420" x2="580" y2="420"/>\n <!-- y = 460, gap [200,240] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="460" x2="200" y2="460"/>\n <line x1="240" y1="460" x2="580" y2="460"/>\n <!-- y = 500, gap [320,360] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="500" x2="320" y2="500"/>\n <line x1="360" y1="500" x2="580" y2="500"/>\n <!-- y = 540, gap [240,280] -->\n <line x1="20" y1="540" x2="240" y2="540"/>\n <line x1="280" y1="540" x2="580" y2="540"/>\n </g>\n</svg>

Claude 4 Sonnet

Sonnet took 11 seconds and 860 tokens

Usage(requests=1, request_tokens=22, response_tokens=838, total_tokens=860, details={'cache_creation_input_tokens': 0, 'cache_read_input_tokens': 0, 'input_tokens': 22, 'output_tokens': 838})

<svg width="400" height="400" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">\n <rect width="400" height="400" fill="white" stroke="black" stroke-width="2"/>\n \n <!-- Outer walls -->\n <rect x="0" y="0" width="400" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="0" y="380" width="400" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="0" y="0" width="20" height="400" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="380" y="0" width="20" height="400" fill="black"/>\n \n <!-- Start opening -->\n <rect x="0" y="20" width="20" height="20" fill="white"/>\n \n <!-- End opening -->\n <rect x="380" y="360" width="20" height="20" fill="white"/>\n \n <!-- Internal walls -->\n <rect x="60" y="20" width="20" height="100" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="140" y="20" width="20" height="80" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="220" y="20" width="20" height="120" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="300" y="20" width="20" height="60" fill="black"/>\n \n <rect x="20" y="160" width="80" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="160" y="140" width="100" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="320" y="100" width="60" height="20" fill="black"/>\n \n <rect x="120" y="180" width="20" height="80" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="280" y="160" width="20" height="100" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="40" y="220" width="60" height="20" fill="black"/>\n \n <rect x="180" y="200" width="80" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="320" y="180" width="20" height="60" fill="black"/>\n \n <rect x="20" y="280" width="60" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="160" y="260" width="20" height="80" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="200" y="280" width="60" height="20" fill="black"/>\n \n <rect x="100" y="320" width="40" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="220" y="320" width="80" height="20" fill="black"/>\n \n <rect x="60" y="360" width="100" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="200" y="360" width="60" height="20" fill="black"/>\n \n <!-- Additional maze complexity -->\n <rect x="340" y="280" width="20" height="60" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="260" y="240" width="40" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="80" y="120" width="40" height="20" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="360" y="140" width="20" height="40" fill="black"/>\n <rect x="140" y="300" width="20" height="40" fill="black"/>\n</svg>

The maze generated by Sonnet also is on the easier end of mazes.

Though sonnet seems to be a lost faster and consumes far fewer tokens. From this test and what I’ve seen on the internet, for most of your use-cases, there shouldn’t be a significant jump in using GPT-5 over Sonnet or even Gemini 2.5 pro.

Let me know if you want me to test GPT-5 vs Gemini 2.5 pro or any other model.