In Part 1 of this series, we covered how you can use lag features and simple linear regression models to do time series forecasting, but that is very simple and you cannot capture trends using that model which is non-linear.

So we will be discussing different types of moving averages you can calculate in python and how they are helpful.

Simple Moving Average

# Loading Libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_theme()

#Using the available dowjones data in seaborn

dowjones = sns.load_dataset("dowjones")

dowjones.head()

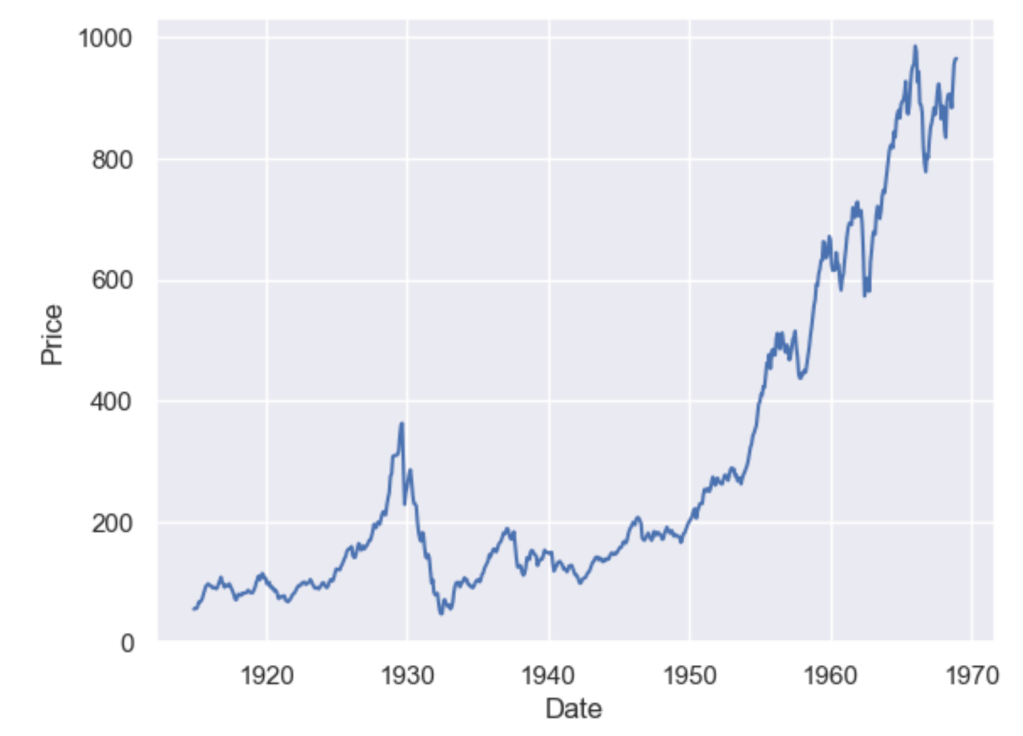

sns.lineplot(data=dowjones, x="Date", y="Price")

A simple moving average (SMA) calculates the average of a selected range of values, by the number of periods in that range. The most typical moving averages are 30-day, 50-day, 100-day and 365 day moving averages. Moving averages are nice cause they can determine trends while ignoring short-term fluctuations. One can calculate the sma by simply using

DataFrame.rolling(window, min_periods=None, center=False, win_type=None, on=None, axis=0, closed=None, step=None, method='single')

dowjones['sma_30'] = dowjones['Price'].rolling(window=30, min_periods=1).mean()

dowjones['sma_50'] = dowjones['Price'].rolling(window=50, min_periods=1).mean()

dowjones['sma_100'] = dowjones['Price'].rolling(window=100, min_periods=1).mean()

dowjones['sma_365'] = dowjones['Price'].rolling(window=365, min_periods=1).mean()

sns.lineplot(x="Date", y="value", legend='auto', hue = 'variable', data = dowjones.melt('Date'))

As you can see the higher the value of the window, the lesser it is affected by short-term fluctuations and it captures long-term trends in the data. Simple Moving Averages are often used by traders in the stock market for technical analysis.

Exponential Moving Average

Simple moving averages are nice, but they give equal weightage to each of the data points, what if you wanted an average that will give higher weight to more recent points and lesser to points in the past. In that case, what you want is to compute the exponential moving average (EMA).

$latex EMA_{Today} = Value_{Today}(\frac{smoothing}{1+Days}) + EMA_{Yesterday}(1 – \frac{Smoothing}{1+Days})$

To calculate this in pandas you just have to use the pandas ewm function.

dowjones['ema_50'] = dowjones['Price'].ewm(span=50, adjust=False).mean()

dowjones['ema_100'] = dowjones['Price'].ewm(span=100, adjust=False).mean()

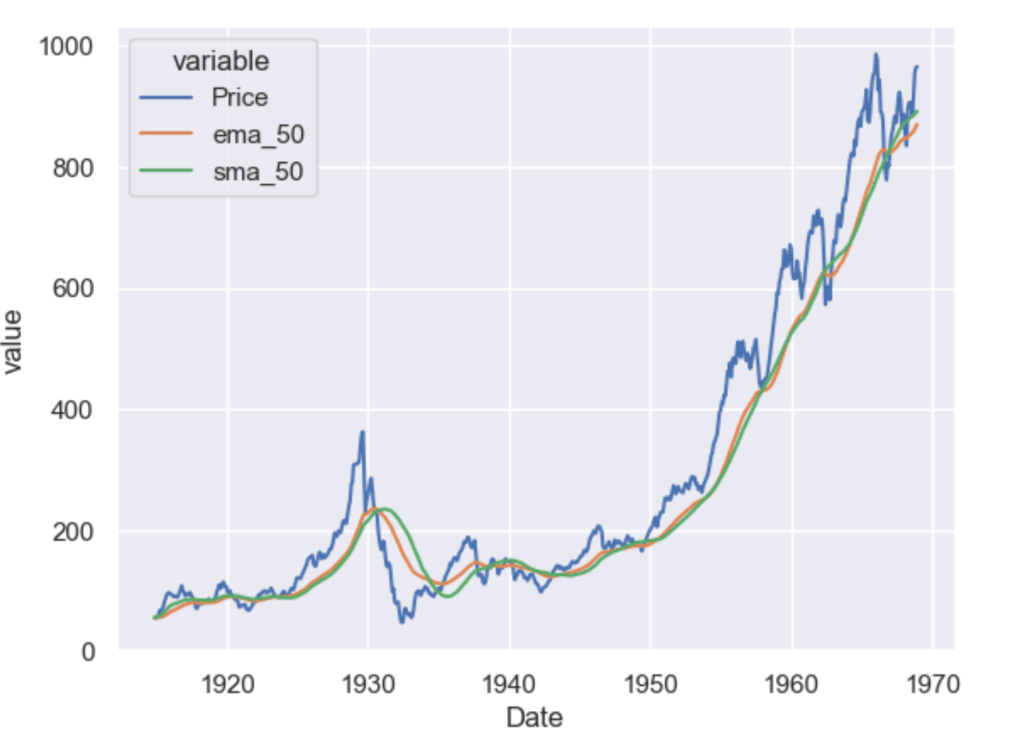

sns.lineplot(x="Date", y="value", legend='auto', hue = 'variable',

data = dowjones[['Date', 'Price','ema_50', 'sma_50']].melt('Date'))

As you can see the ema_50 follows the Price chart more closely than the sma_50 and is more sensitive to the recent data points.

Which moving average you should use as a feature of your forecasting model is a question mostly dependent on the use case. However, you will often use some kind of moving average as a feature or to visualise long-term or short-term trends in your data.

In Part 3 we explore trends and seasonality and how can you identify them in your data.