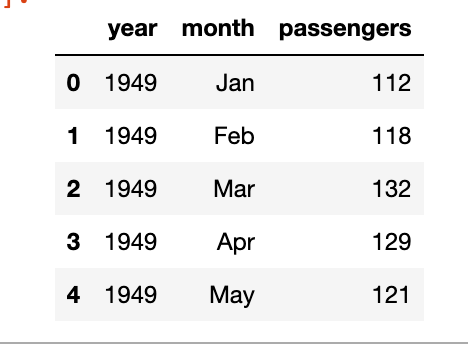

In Part III, we saw trends and seasonality in time series data and how can we decompose it using statsmodel.

In this part we will learn about stationarity in time series data and how can we test it using Augmented Dicky Fuller Test.

Stationarity is a fundamental concept in time series analysis. It refers to the statistical properties of a time series remaining constant over time. In a stationary time series, the mean, variance, and autocovariance structure do not change with time.

There are three main components of stationarity:

- Constant Mean: The mean of the time series should remain constant over time. This means that the average value of the series does not show any trend or systematic patterns as time progresses.

- Constant Variance: The variance (or standard deviation) of the series should remain constant over time. It implies that the spread or dispersion of the data points around the mean should not change as time progresses.

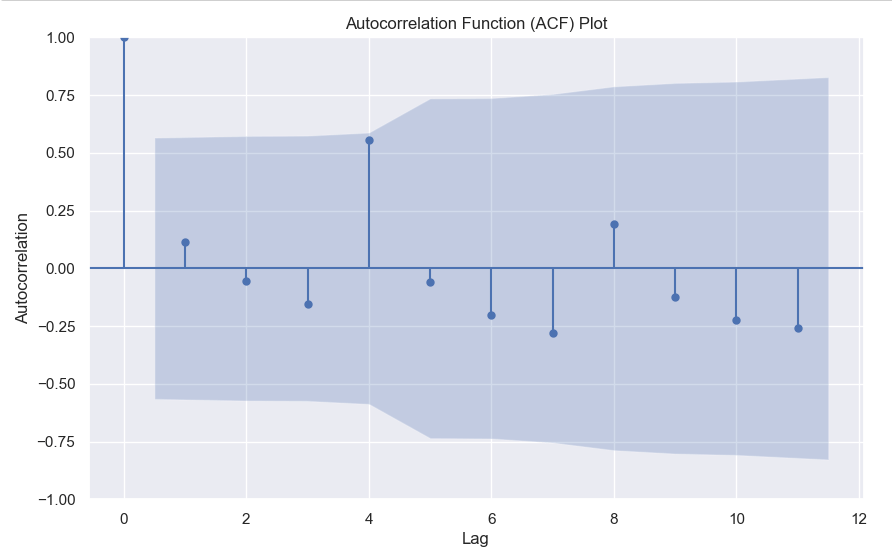

- Constant Autocovariance: The autocovariance between any two points in the time series should only depend on the time lag between them and not on the specific time at which they are observed. Autocovariance measures the linear relationship between a data point and its lagged values. In a stationary series, the autocovariance structure remains constant over time.

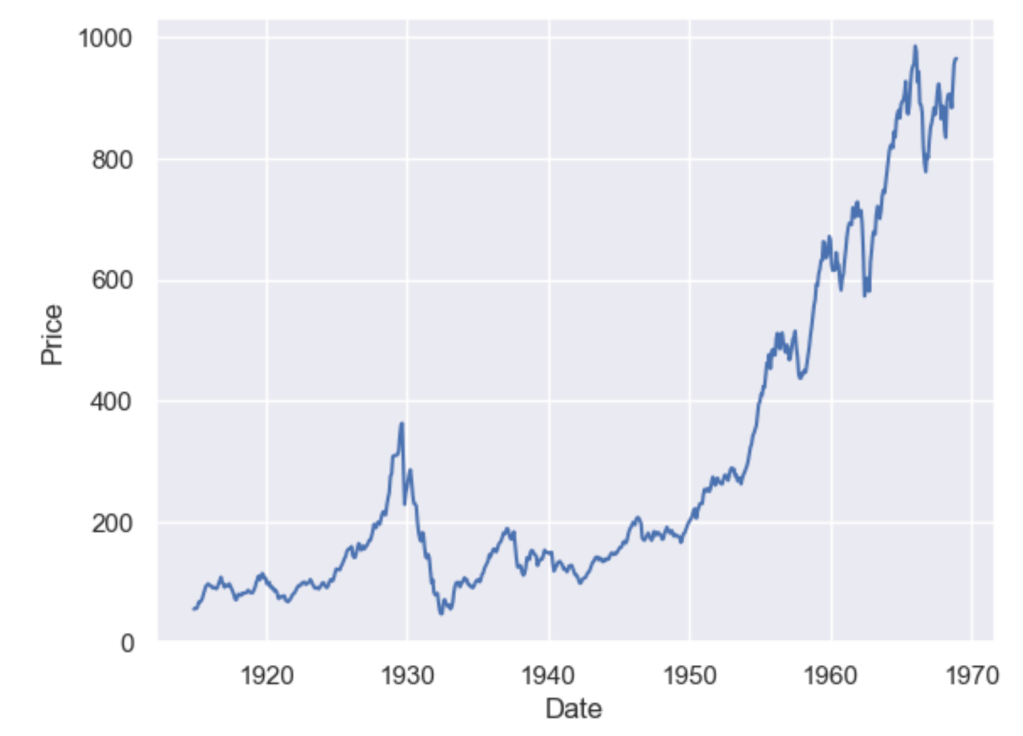

Why is stationarity important in time series analysis? Stationarity is a crucial assumption for many time series models and statistical tests. If a time series violates the stationarity assumption, it can lead to unreliable and misleading results. For example, non-stationary series may exhibit trends, seasonality, or other time-dependent patterns that can distort statistical inference, prediction, and forecasting.

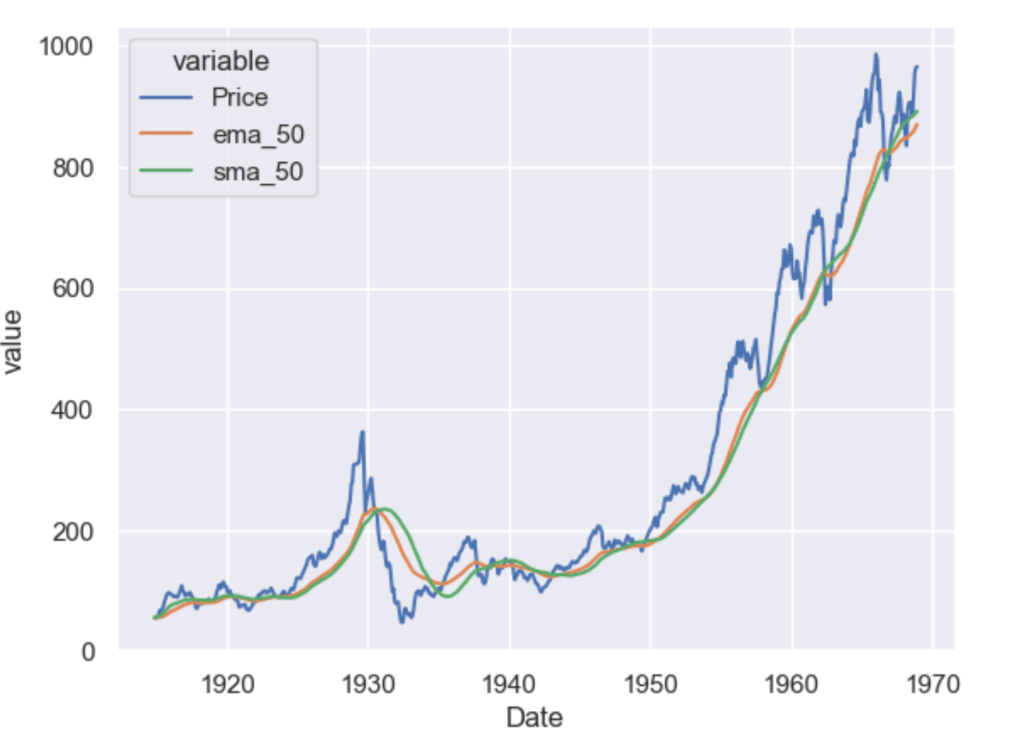

To analyze non-stationary time series, researchers often use techniques like differencing to transform the series into a stationary form. Differencing involves computing the differences between consecutive observations to remove trends or other time-dependent patterns. Other methods, such as detrending or deseasonalizing, can also be employed depending on the specific characteristics of the series.

It is important to note that while stationarity is desirable for many time series models, there are cases where non-stationary time series analysis is appropriate, such as when studying trending or seasonal data. However, in such cases, specialized models and techniques designed for non-stationary series need to be employed.

Testing for Stationarity

In Python, you can use various statistical tests to check for stationarity in a time series. One commonly used test is the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test. The statsmodels library provides an implementation of the ADF test, which can be used to assess the stationarity of a time series.

Here’s an example of how to perform the ADF test in Python:

import pandas as pd

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import adfuller

# Create a time series dataset

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

# Perform the ADF test

result = adfuller(data)

# Extract the test statistic and p-value

test_statistic = result[0]

p_value = result[1]

# Print the results

print("ADF Test Statistic:", test_statistic)

print("p-value:", p_value)

The values come out to be

ADF Test Statistic: 0.0 p-value: 0.958532086060056

The ADF test statistic measures the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis of non-stationarity. A more negative (i.e., lower) test statistic indicates stronger evidence in favor of stationarity. The p-value represents the probability of observing the given test statistic if the null hypothesis of non-stationarity were true. A small p-value (typically less than 0.05) suggests rejecting the null hypothesis and concluding that the series is stationary. In this example we can clearly see that the null hypothesis was not rejected, meaning that the time series is not stationary.

In the next part we will cover how we can convert non-stationary time series data to stationary time series.