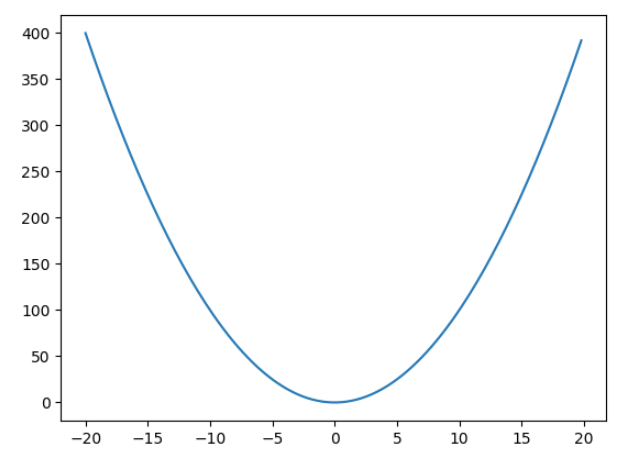

How will you minimise this function –

The mathematical solution will be to find the derivative, then solve the equation, , which gives the solution as x = 0. But what if you don’t know this and need to rely on a method which can reach the minimum of a function iteratively. That is what gradient descent does.

Gradient descent as the name suggests is like slowly descending down the mountain that is the loss function but in an iterative manner. We always take a small step in the opposite direction of the gradient. If the gradient is positive, we take a negative step and if the gradient is negative then we take a positive step.

So in this example suppose we have to minimise and we start off with an initial value say 7. Then we we will update the value of x as –

x_new = x_old + (-)*x_old*lr

where lr is the learning rate. Tuning this value is crucial is how fast we reach the minimum, or if we overshoot the minimum and never reach it.

Let’s take an example in python –

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

import numpy as np

def f(x):

return x**2

def derivative(x):

return 2*x

y = [f(x) for x in np.arange(-20,20,0.2)]

x = np.arange(-20,20,0.2)

plt.plot(x,y)

value = 7

lr = 0.1

derivatives = []

values = []

for i in range(9):

values.append(value)

derivatives.append(derivative(value))

value = value - lr*derivative(value)

# List of points and derivatives

points = [(x,f(x)) for x in values]

# Create a 9x9 subplot grid

fig, axs = plt.subplots(3, 3, figsize=(9, 9))

# Plot the main plot (x^2) in the top-left subplot

axs[0, 0].plot(x, y, label='$x^2$', color='blue')

axs[0, 0].legend()

# Iterate over points and derivatives to create subplots

for i, (point_x, point_y) in enumerate(points):

# Calculate the line passing through the point with the slope from the derivatives list

slope = derivatives[i]

line_y = x + slope * (x - point_x)

axs[i//3, i%3].plot(x, y, color='blue')

# Plot the point

axs[i//3, i%3].plot(point_x, point_y, marker='x', markersize=10, color='red', label='Point')

# Plot the line passing through the point with the specified slope

axs[i//3, i%3].plot(x, line_y, linestyle='--', color='green', label=f'Slope = {slope}')

# Set titles for subplots

axs[i//3, i%3].set_title(f'Point at ({np.round(point_x,2)}, {np.round(point_y,2)})')

# Adjust layout for better visualization

plt.tight_layout()

# Show the plot

plt.show()

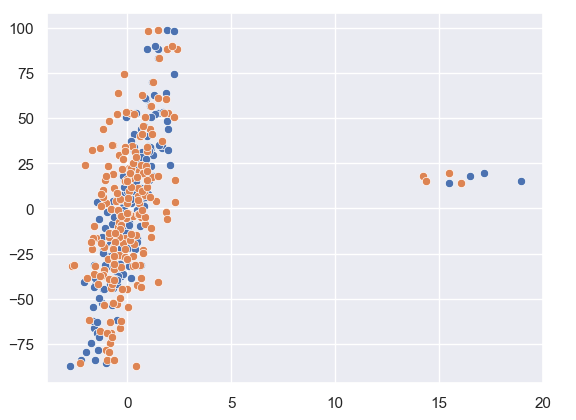

Here we see that with a learning rate of 0.1 and a starting value of 7 and in 9 steps we were able to reach 1.17, pretty close to the minimum of 0, but not quite so, if we change the lr to 0.3, let’s see what happens.

The minimum of 0 was reached within 9 steps.

But what happens if we make the lr 1 –

Here you can see that the value keeps oscillating between 7 and -7, and thus having a large learning rate also can be harmful when using ML models that use gradient descent.

Hopefully this example gave you a visual guide on how gradient descent works.