Suppose you’re building a classification model on an imbalanced dataset and you want to have other measures for your model other than accuracy, F1-score, and ROC-AUC curve, what else can you measure to be confident in your results. The answer is Cohen’s kappa.

Cohen’s Kappa is a statistical measure that quantifies the level of agreement between two annotators or, in the context of ML, the agreement between the model’s predictions and the true labels. It accounts for the possibility of agreement occurring by chance, providing a more nuanced evaluation than traditional accuracy metrics.

The Formula:

The formula for Cohen’s Kappa is –

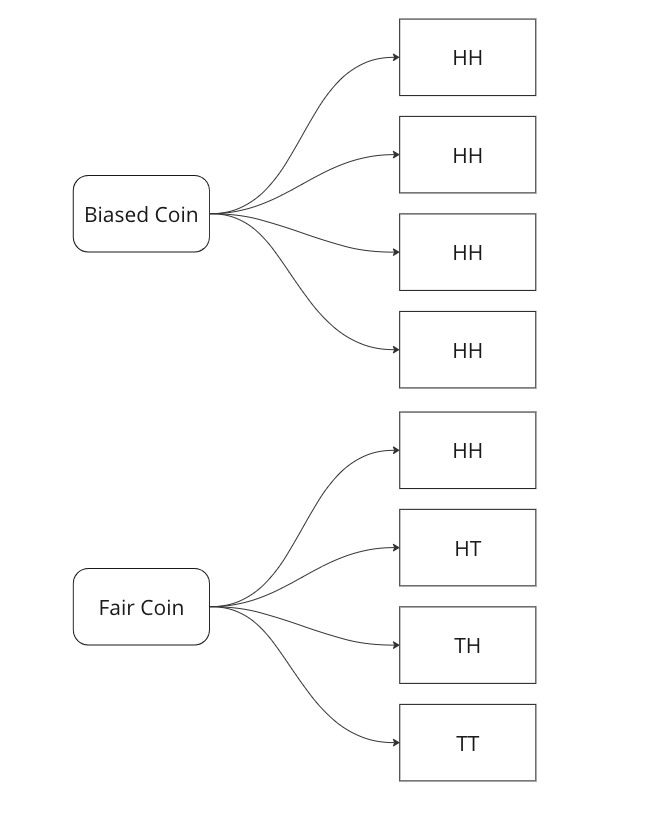

Where is the observed agreement between the model’s predictions and true labels and

is the expected agreement by chance.

Let’s take an example to understand this better. A binary classification scenario where you’re building a spam email classifier. The task is to distinguish between spam and non-spam (ham) emails. We’ll use a simple logistic regression model for this example.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, confusion_matrix, cohen_kappa_score

# Sample data for spam and non-spam emails

data = [

("Get rich quick! Claim your prize now!", "spam"),

("Meeting at 3 pm in the conference room.", "ham"),

("Exclusive offer for you!", "spam"),

("Reminder: Project deadline tomorrow.", "ham"),

# ... more data ...

]

# Split the data into training and testing sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

[text for text, label in data],

[label for text, label in data],

test_size=0.2,

random_state=42

)

# Vectorize the text data

vectorizer = CountVectorizer()

X_train_vec = vectorizer.fit_transform(X_train)

X_test_vec = vectorizer.transform(X_test)

# Train a logistic regression classifier

classifier = LogisticRegression()

classifier.fit(X_train_vec, y_train)

# Make predictions on the test set

y_pred = classifier.predict(X_test_vec)

# Evaluate the model

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

conf_matrix = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred)

kappa_score = cohen_kappa_score(y_test, y_pred)

# Print the results

print(f"Accuracy: {accuracy}")

print(f"Confusion Matrix:\n{conf_matrix}")

print(f"Cohen's Kappa: {kappa_score}")

After this, you get a kappa of 1, which means that it’s an excellent model and there is no variability that can be attributed to chance. Be aware that this is an ideal scenario.

Another scenario is that you get a score of 0, meaning that the model’s performance is no better than random chance, that is your features don’t capture any meaningful patterns in the data.

In the context of model evaluation:

Kappa scores closer to 1 indicate a high level of agreement and are generally considered desirable.

Kappa scores around 0 or below suggest poor agreement, and the model’s predictions might not be reliable.

It’s essential to interpret Cohen’s Kappa alongside other evaluation metrics, such as accuracy, precision, recall, and the confusion matrix, to comprehensively understand the model’s performance. Additionally, the interpretation of Kappa may vary depending on the specific problem and the level of difficulty in the classification task.