NOTE – The article is under progress, I’ll be uploading the Youtube and linking the Kaggle notebook soon.

Most often the data you get in the real world for classification tasks is imbalanced. You always end up dealing with the imbalance on your own before passing it through models, but what if there was a python package, built on top of scikit-learn that could do the heavy lifting for you, that’s exactly what imbalanced-learn (imblearn) is.

I was inspired to use this package due this Kaggle Competition. I’ve linked the notebook in this post so you can refer it.

But I’ll highly encourage you to watch the Youtube video below where I go over how I leverage imblearn with XgBoost to get a very good and balanced model as a baseline with very little effort.

There are many ways imblearn which you can leverage to balance your data.

The first is Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE)

To use this, all you have to do is to invoke the following code below –

from imblearn.over_sampling import SMOTE, ADASYN

X_smote, y_smote = SMOTE().fit_resample(X, y)

After this your minortity class will up-sampled. There are also variations of SMOTE which you can use to balance your data using the library.

Similarly you can call X_adasyn, adasyn = ADASYN().fit_resample(X,y) to oversample your data.

There is also another function which will balance your data, but do know that this will take a lot of time to execute, and that is SMOTEENN (Over-sampling using SMOTE and cleaning using ENN).

To call this you again have to use these two lines of code and let imblearn do the heavy lifting for you.

from imblearn.combine import SMOTEENN

X_balanced, y_balanced = SMOTEENN().fit_resample(X,y)

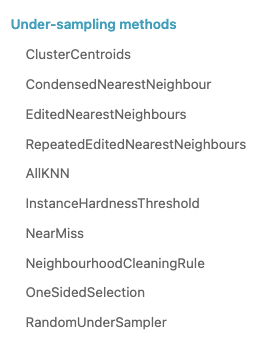

You can also use any one of the following methods to undersample your data, note that undersampling using k-nearest neighbour methods will take some time.

Again all you have to do is use <undersampling method>.fit_resample(X,y)

Once your data is ready, you can tune your model. The best thing about the competition was that the features were generated through some sort of PCA transformation, so we could easily use techniques like SMOTE, ADASYN to train the models. I did not use SMOTEENN as the notebook on Kaggle started to time out.

Here is the link to the starter notebook, you can play around with it and try other sampling methods in imblearn.

Hopefully, this post gave you insights on leveraging imblearn in your imbalanced classification problems.