Today, we will be going over how you can match two DataFrames using RapidFuzz and Pandas.

Suppose that you’ve two DataFrames, one having the product_id and the other having the product_price, with the key being the name. Since, names can be written differently, you’ve to match them.

| name | product_id |

| M.D. Luffy | A |

| R. Zoro | B |

| Sanji | C |

| Nami | D |

| Naruto | E |

| name | product_price |

| Monkey D. Luffy | 100 |

| Roronoa Zoro | 10 |

| Sannnji | 500 |

| Nami Chain | 1000 |

| Jiraiya | 300 |

Since we can see that the name is written differently in the tables, we can’t do a direct left join using name as the key. We will be using fuzzy join using rapidfuzz library.

# Importing the libraries

import pandas as pd

from rapidfuzz import fuzz

from rapidfuzz.process import cdist, extract

We will be using the extract process to find the closest matching key from the second table to use as merge in the first table.

df1 = pd.DataFrame({"name": ["M.D. Luffy",

"R. Zoro",

"Sanji",

"Nami",

"Naruto"],

"product_id":["A", "B", "C", "D", "E"]})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({"name": ["Monkey D. Luffy",

"Roronoa Zoro",

"Sannnji",

"Nami Chan",

"Jiraiya"],

"product_price":[100,10,500,1000,300]})

df1['join_key_tuple'] = df1['name'].apply(lambda x: extract(query = x, choices =df2['name'], score_cutoff=80))Here the query is the string you want to match, choices are all the choices to match against. You can pass a custom scorer as well, but here we are using the defualt scorer, and lastly we’re passing a cutoff which we will use to determine a successful match.

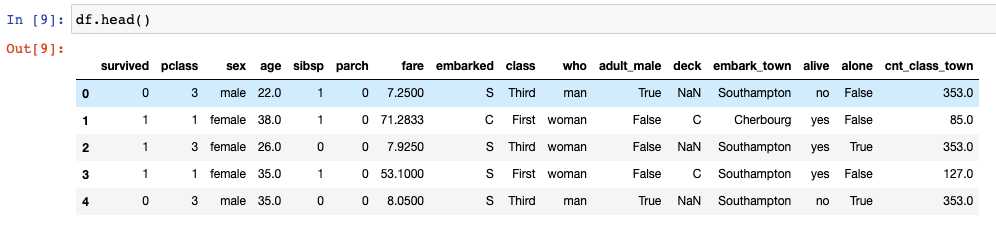

name product_id join_key_tuple

0 M.D. Luffy A [(Monkey D. Luffy, 85.5, 0)]

1 R. Zoro B [(Roronoa Zoro, 85.5, 1)]

2 Sanji C [(Sannnji, 83.33333333333334, 2)]

3 Nami D [(Nami Chan, 90.0, 3)]

4 Naruto E []We can now extract the key to join from the returned tuple and make the join to have the price of the product against the product_id.

df1["join_key"] = df1["join_key_tuple"].apply(lambda x: x[0][0] if x else np.nan)

df1.merge(df2, how = "left", left_on = "join_key", right_on ="name")

This way you can do fuzz join on two pandas dataframe.