Ever seen an AI agent go from stumbling around cluelessly to mastering its environment, making perfect moves every single time? In this blog post, we’ll explore how to train an agent to do just that, transforming random, chaotic actions into smooth, optimal choices. We’ll dive into the fascinating world of Q-learning and discover how it empowers AI agents to learn and adapt. In case you want to follow along, here is the link to the collab notebook.

What Is Q-Learning ?

Q-learning is a type of reinforcement learning where an agent learns to make optimal decisions by interacting with its environment. The agent explores its surroundings, tries different actions, and observes the outcomes. It uses a Q-table to store Q-values, which represent the expected reward for taking a specific action in a given state. Over time, the agent updates its Q-values based on its experiences, gradually learning the best actions to take in each situation.

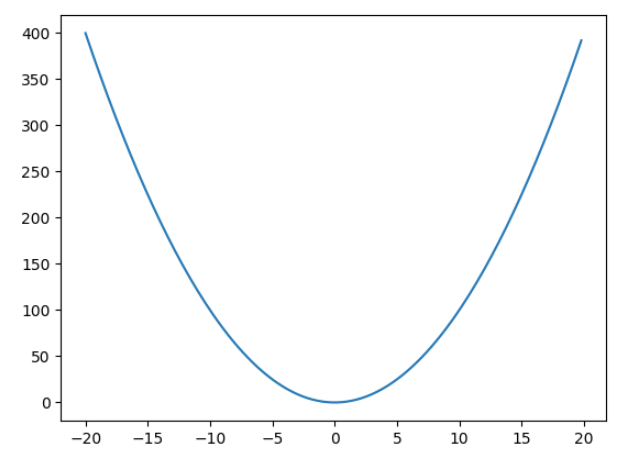

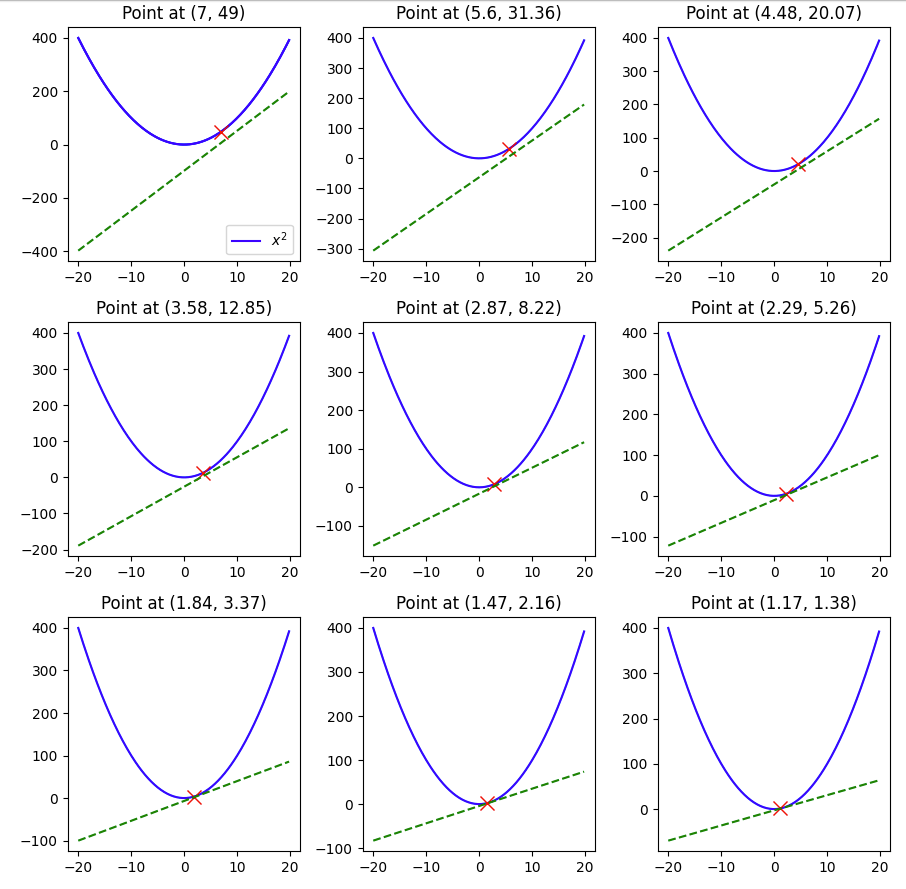

The Q-value update formula takes in our former estimate of the Q-value and then adds the temporal difference error, which is crucial for correctly adjusting our predictions based on new information. We multiply this value by a learning rate to take small, manageable steps, akin to the incremental updates we see in machine learning algorithms, allowing for gradual refinement of our estimates. The Temporal Difference Error is particularly significant as it comprises not just the immediate reward received from a given action, but also includes the discounted estimate of the optimal Q-value in the next state that our selected action will lead us into; this next step’s predicted value is critical as it influences our future decisions. This entire process is essential for the learning agent to adapt effectively to its environment, correction of biases in the initial Q-value estimates, and thus improving the overall decision-making strategy. By subtracting this former estimate of the Q-value from the combined factors, we arrive at a refined estimate that enhances the agent’s ability to predict and maximize long-term rewards in a dynamic setting.

The Frozen Lake Environment

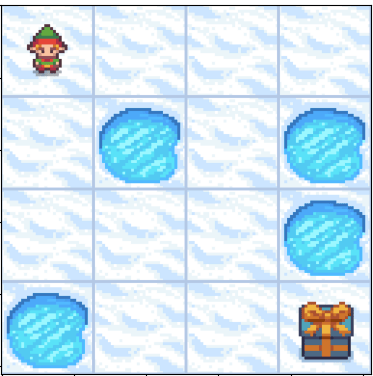

Enough of theory, now it’s time to train our agent on the Frozen Lake Environment. Imagine a frozen lake with slippery patches. Our agent’s goal is to navigate across the lake without falling into any holes. The agent can move up, down, left, or right, but the slippery surface makes its actions unpredictable. This simple environment provides a great starting point for understanding Q-learning. We will go over the training on the non-slipper environment. To see how the agent performs in the slippery environment, you can see the YouTube video for this.

The first thing we will have to do is to initialize the environment.

# Importing libraries

import gymnasium as gym

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

np.set_printoptions(precision=3)

env = gym.make('FrozenLake-v1', desc=None, map_name="4x4", is_slippery=False, render_mode="rgb_array")

print(f"There are {env.action_space.n} possible actions")

print(f"There are {env.observation_space.n} states")

>>>There are 4 possible actions

>>>There are 16 states

We can see that our world is 4×4 in size and thus has 16 possible states and there are 4 possible actions – up, down, left and right. We can take a look at the world.

The goal of our agent is to reach the prize at the bottom-right. We can clearly see that it can do so by either going right->right->down->down->down->right or by following down->down->right->right->down->right. But how do we train the agent to come up with either of these path on its own.

We do so by initially letting the agent explore the environment randomly, trying different actions to see what happens, without any predefined strategy guiding its decisions. This phase of exploration is crucial, as it allows the agent to gather diverse experiences and build a foundational understanding of the environment’s dynamics. As it gains experience over time, it starts exploiting its learned knowledge, choosing actions with higher Q-values that have been identified as beneficial through previous trials. This shift from exploration to exploitation represents a significant turning point in the agent’s learning process, where it leverages its accumulated data to make more informed decisions. Throughout its journey, the agent balances exploration and exploitation to ensure it both discovers new strategies and utilizes its existing knowledge effectively. By continuously adjusting this balance, the agent enhances its performance, ultimately leading to more efficient learning and improved decision-making capabilities in complex scenarios.

To do so let’s establish some helper functions first –

def get_action(epsilon, state, q_table):

if np.random.rand() < epsilon:

return np.random.randint(0, env.action_space.n)

else:

return np.argmax(q_table[state])

def get_td_error(state, next_state, action, reward, q_table):

former_q_est = q_table[state,action]

td_target = reward+ gamma*np.max(q_table[next_state])

td_error = td_target - former_q_est

return td_error

# As seen, we first define the Q-table and during the training epochs we update this value.

q_table = np.zeros((env.observation_space.n, env.action_space.n))

We created two functions, The first function, get_action, determines the action based on epsilon, which controls the randomness of our actions.. Initially during training we keep the epsilon very high and lower it as the agent learns. The second function, get_td_error, calculates the temporal difference error after each step. We also created our q-table which is a combination n_states x n_actions= 16×4.

We also have to establish training hyper-parameters.

num_epochs = 1000

gamma = 0.99

lr = 0.1

decay_rate=0.99

epsilon = 1

During training, in each epoch we update our q-table after each action. The epoch is done if we either fall into the hole or get to the prize. After the episode is done we decay the epsilon a bit and repeat the process again. After the training is done our q-table should have converged to optimal q-values for each state-action pair.

for i in range(num_epochs):

state, _ = env.reset()

done = False

while not done:

action = get_action(epsilon, state, q_table)

next_state, reward, done, _, _ = env.step(action)

td_error = get_td_error(state, next_state, action, reward, q_table)

q_table[state, action] = q_table[state, action] + lr*td_error

state = next_state

epsilon*=decay_rate

Now that we’ve trained our agent, let’s see how it’s action looks like. The code for creating the animation is in the collab notebook.

We can see that it always now follows the optimal path.

Conclusion

Q-learning is a powerful technique for training AI agents to make optimal decisions. By interacting with their environment and learning from their experiences, agents can master even complex tasks. As we’ve seen, the environment plays a crucial role in shaping the agent’s behavior.

However, in complex environments with a vast number of states, traditional Q-learning becomes impractical. That’s where deep Q-learning comes in. By using deep neural networks, we can approximate Q-values without relying on an enormous Q-table. Stay tuned for our next blog post, where we’ll explore the intricacies of deep Q-learning.