First, a shout-out to Santiago, whose tweet inspired this post.

In the realm of machine learning, ensuring that models perform well not only on training data but also on unseen test data is crucial. A common challenge that arises is the difference in data distribution between training and testing datasets, known as dataset shift. This discrepancy can significantly degrade the performance of a model when deployed in real-world scenarios. To tackle this issue, researchers and practitioners have developed various methods to detect and quantify differences in data distribution. One innovative approach is the adversarial method, which leverages concepts from adversarial training to assess and address these differences.

Understanding Dataset Shift

Before diving into the adversarial methods, it is essential to understand what dataset shift entails. Dataset shift occurs when the joint distribution of inputs and outputs differs between the training and testing phases. This shift can be categorised into several types, including covariate shift, prior probability shift, and concept shift, each affecting the model in different ways.

- Covariate Shift: The distribution of input features changes between the training and testing datasets.

- Prior Probability Shift: The distribution of the output variable changes.

- Concept Shift: The relationship between the input features and the output variable changes.

Detecting and correcting for these shifts is crucial for developing robust machine learning models.

Adversarial Methods for Detecting Dataset Shift

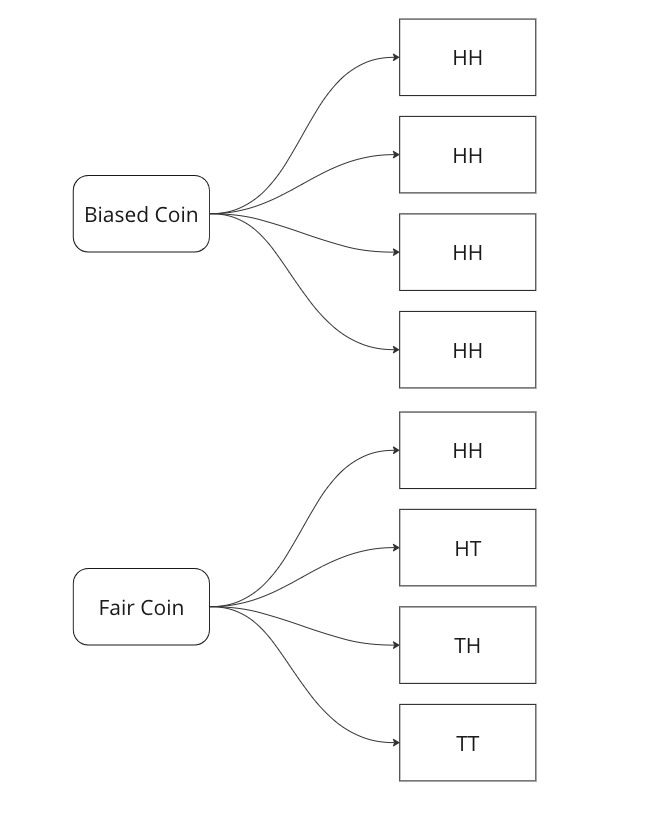

Adversarial methods for dataset shift detection are inspired by adversarial training in neural networks, where models are trained to be robust against intentionally crafted malicious input. Similarly, in dataset shift detection, these methods involve creating a scenario where a model tries to distinguish between training and testing data based on their data distributions.

The way to do this is –

- Combine your train and test data.

- Create a new column, where you label training data as 1 and test data as 0.

- Train a classifier on this using your new column as the target.

If the data in both train and test comes from the same distribution, the AUC will be close to 0.5, but if they are from different distributions, then the model will learn to differentiate the data points and the AUC will be close to 1.

Example

In this example, we will have training data as height and weight in metres and kilograms, and in the test data, we will have the same data but in centimetres and grams. Then if we train a simple logistic regression to learn on the dummy target, which is 1 on the training set and 0 on test data, given that we are not scaling the variables, the model should have an AUC close to 1.

#Loading required libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

Then we define our features for train and test

# Set random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

# Generate synthetic data

# Training data (height in meters, weight in kilograms)

train_height = np.random.normal(1.75, 0.1, 1000) # Average height 1.75 meters

train_weight = np.random.normal(70, 10, 1000) # Average weight 70 kg

# Test data (height in centimeters, weight in grams)

test_height = train_height * 100 # Convert meters to centimeters

test_weight = train_weight * 1000 # Convert kilograms to grams

Once we’ve our features defined, all we need to do is create a training dataset, train our classifier and check the AUC score.

# Combine data into feature matrices

X_train = np.column_stack((train_height, train_weight))

X_test = np.column_stack((test_height, test_weight))

# Create labels: 1 for training data, 0 for test data

y_train = np.ones(X_train.shape[0])

y_test = np.zeros(X_test.shape[0])

# Combine into a single dataset

X = np.vstack((X_train, X_test))

y = np.concatenate((y_train, y_test))

# Train logistic regression model

model = LogisticRegression()

model.fit(X, y)

# Predict probabilities for ROC AUC calculation

y_pred_proba = model.predict_proba(X)[:, 1]

# Calculate AUC

auc = roc_auc_score(y, y_pred_proba)

print(f"The AUC is: {auc:.2f}")

The AUC here comes out to be 1.0 as expected. Since the train and test data comes from different distributions, the model was easily able to identify the difference in the distribution between train and test.

Using this approach you can also easily test whether the train and test data come from the same distribution.